by Florence Sullivan, MSc student

Our third day aboard the Oceanus began in the misty morning fog before the sun even rose. We took the first CTD cast of the day at 0630am because the physical properties of the water column do not change much with the arrival of daylight. Our ability to visually detect marine mammals, however, is vastly improved with a little sunlight, and we wanted to make the best use of our hours at sea possible.

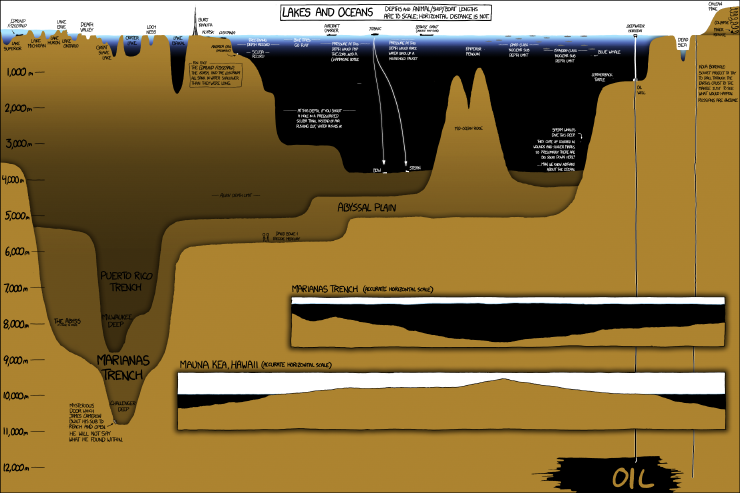

Our focus on day three was the Astoria canyon – a submarine feature just off the Oregon and Washington coast. Our first oceanographic station was 40 miles offshore, and 1300 meters deep, while the second was 20 miles offshore and only 170 meters deep. See the handy infographic below to get a perspective on what those depths mean in the grand scheme of things. From an oceanographic perspective, the neatest finding of the day was our ability to detect the freshwater plume coming from the Columbia River at both those stations despite their distance from each other, and from shore! Water density is one of the key characteristics that oceanographers use to track parcels of water as they travel through the ocean conveyor belt. Certain bodies of water (like the Mediterranean Sea, or the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans) have distinct properties that allow us to recognize them easily. In this case, it was very exciting to “sea” the two-layer system we had gotten used to observing overlain with a freshwater lens of much lower salinity, higher temperature, and lower density. This combination of freshwater, saltwater, and intriguing bathymetric features can lead to interesting foraging opportunities for marine megafauna – so, what did we find out there?

Morning conditions were almost perfect for marine mammal observations – glassy calm with low swell, good, high, cloud cover to minimize glare and allow us to catch the barest hint of a blow….. it should come as no surprise then, that the first sightings of the day were seabirds and tuna!

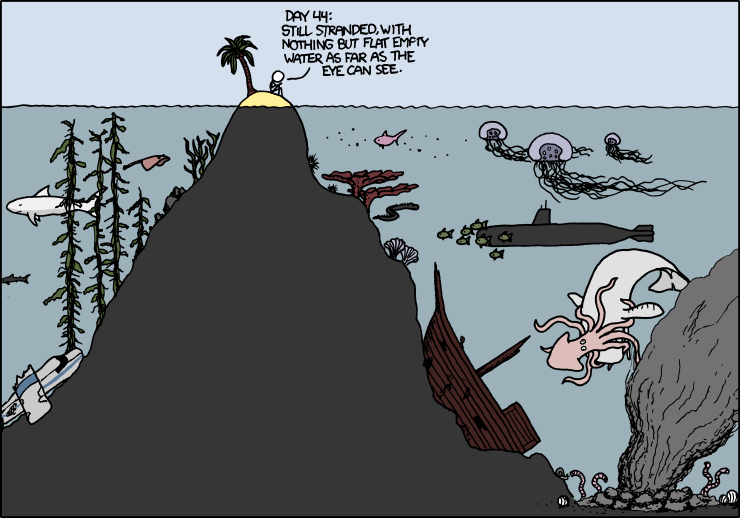

One of the best things about being at sea is the ability to look out at the horizon and have nothing but water staring back at you. It really drives home all the old seafaring superstitions about sailing off the edge of the world. This close to shore, and in such productive waters, it is rare to find yourself truly alone, so when we spot a fishing trawler, there’s already a space to note it in the data log. Ships at sea often have “follower” birds – avians attracted by easy meals as food scraps are dumped overboard. Fishing boats usually attract a lot of birds as fish bycatch and processing leftovers are flushed from the deck. The birders groan, because identification and counts of individuals get more and more complicated as we approach other vessels. The most thrilling bird sighting of the day for me were the flocks of a couple hundred fork-tailed storm petrels.

I find it remarkable that such small birds are capable of spending 80% of their life on the open ocean, returning to land only to mate and raise a chick. Their nesting strategy is pretty fascinating too – in bad foraging years, the chick is capable of surviving for several days without food by going into a state of torpor. (This slows metabolism and reduces growth until an adult returns.)

Just because the bird observers were starting to feel slightly overwhelmed, doesn’t mean that the marine mammal observers stopped their own survey. The effort soon paid off with shouts of “Wait! What are those splashes over there?!” That’s the signal for everyone to get their binoculars up, start counting individuals, and making note of identifying features like color, shape of dorsal fin, and swimming style so that we can make an accurate species ID. The first sighting, though common in the area, was a new species for me – Pacific white sided dolphins!

A pod of thirty or so came to ride our bow wake for a bit, which was a real treat. But wait, it got better! Shortly afterward, we spotted more activity off the starboard bow. It was confusing at first because we could clearly see a lot of splashes indicating many individuals, but no one had glimpsed any fins to help us figure out the species. As the pod got closer, Leigh shouted “Lissodelphis! They’re lissodelphis!” We couldn’t see any dorsal fins, because northern right whale dolphins haven’t got one! Then the fly bridge became absolute madness as we all attempted to count how many individuals were in the pod, as well as take pictures for photo ID. It got even more complicated when some more pacific white sided dolphins showed up to join in the bow-riding fun.

All told, our best estimates counted about 200 individuals around us in that moment. The dolphins tired of us soon, and things continued to calm down as we moved further away from the fishing vessels. We had a final encounter with an enthusiastic young humpback who was breaching and tail-slapping all over the place before ending our survey and heading towards Astoria to make our dock time.

As a Washington native who has always been interested in a maritime career, I grew up on stories of The Graveyard of the Pacific, and how difficult the crossing of the Columbia River Bar can be. Many harbors have dedicated captains to guide large ships into the port docks. Did you know the same is true of the Columbia River Bar? Conditions change so rapidly here, the shifting sands of the river mouth make it necessary for large ships to receive a local guest pilot (often via helicopter) to guide them across. The National Motor Lifeboat School trains its students at the mouth of the river because it provides some of “the harshest maritime weather conditions in the world”. Suffice it to say, not only was I thrilled to be able to detect the Columbia River plume in our CTD profile, I was also supremely excited to finally sail across the bar. While a tiny part of me had hoped for a slightly more arduous crossing (to live up to all the stories you know), I am happy to report that we had glorious, calm, sunny conditions, which allowed us all to thoroughly enjoy the view from the fly bridge.

Finally, we arrived in Astoria, loaded all our gear into the ship’s RHIB (Ridged Hulled Inflatable Boat), lowered it into the river, descended the rope ladder, got settled, and motored into port. We waved goodbye to the R/V Oceanus, and hope to conduct another STEM cruise aboard her again soon.

Now if the ground would stop rolling, that would be just swell.

Last but not least, here are the videos we promised you in Oceanus Day Two – the first video shows the humpback lunge feeding behavior, while the second shows tail slapping. Follow our youtube channel for more cool videos!

You must be logged in to post a comment.