Every college student registers for classes, hoping for academic success. However, college study can be challenging, even for those students who often get As and Bs in elementary and secondary schools (Macalester University, n.d.). Research tells us that lack of time management skills, life challenges that are out of students’ control, content challenges, and not knowing how to learn are among top factors contributing to academic failure in college. (Fetzner, 2013; Texas A&M Today, 2017, Perez, 2019) In this blog, we will examine the importance of teaching college students time management skills, and how we should teach them those skills.

Why should we teach college students time management skills?

Fetzner (2013) reported top 10 ranked reasons students drop courses in college, after surveying over 400 students who dropped at least one online course:

- 7% – I got behind and it was too hard to catch up.

- 2% – I had personal problems (health, job, child care).

- 7% – I couldn’t handle combined study plus work or family responsibilities.

- 3% – I didn’t like the online format.

- 3% – I didn’t like the instructor’s teaching style.

- 8% – I experienced too many technical difficulties.

- 2% – The course was taking too much time.

- 0% – I lacked motivation.

- 3% – I signed up for too many courses and had to cut down on my course load.

- 0% – The course was too difficult.

Student services staff at Oregon State University Ecampus also confirm, based on their daily interactions with online students, that many college students lack time management skills (Perez, 2019). Now that we have realized that many college students lack sufficient time management skills, do we leave it for students to struggle and learn it on their own? Or is there anything we can do to help students develop time management skills so they thrive throughout their college courses? And who can help?

Who can help?

Many higher education professionals, including instructors, instructional designers, advisors, student success coaches, and administrators can help students develop time management skills. For example, at New Student Orientation, there could be a module on time management. Perez (2019) raised a good point that usually New Student Orientation already has too much information to cover, there will be very little room for thorough/sufficient time management training, even though we know it is an area that many of our students need improvement. Advisors can help students with time management skills. Unfortunately, with the current advisor/college students ratio and 15 minutes per student consultation time, that is very unlikely to happen either. Last but not least, instructors can help students with time management skills in every course they teach. If instructors are busy, instructional designers can help with templates or pre-made assignments to give students opportunity to practice time management skills.

How can instructors teach students time management skills?

How could instructors and instructional designers help students from falling behind? A couple crucial solutions are teaching students time management skills and giving students opportunities to plan time for readings, quizzes, writing original discussion posts, responding in discussion forums, working on assignments, homework problems, papers, and projects. Regarding self-hep materials for time-management skill, there are abundant resources on how students could improve time-management skills on their own. Apps and computer programs can help us manage time better. Sabrina Collier (2018) recommended over ten time management apps, including myHomework Student Planner, Trello, Evernote, Pomodoro apps, StayFocused, Remember the Milk, and more.

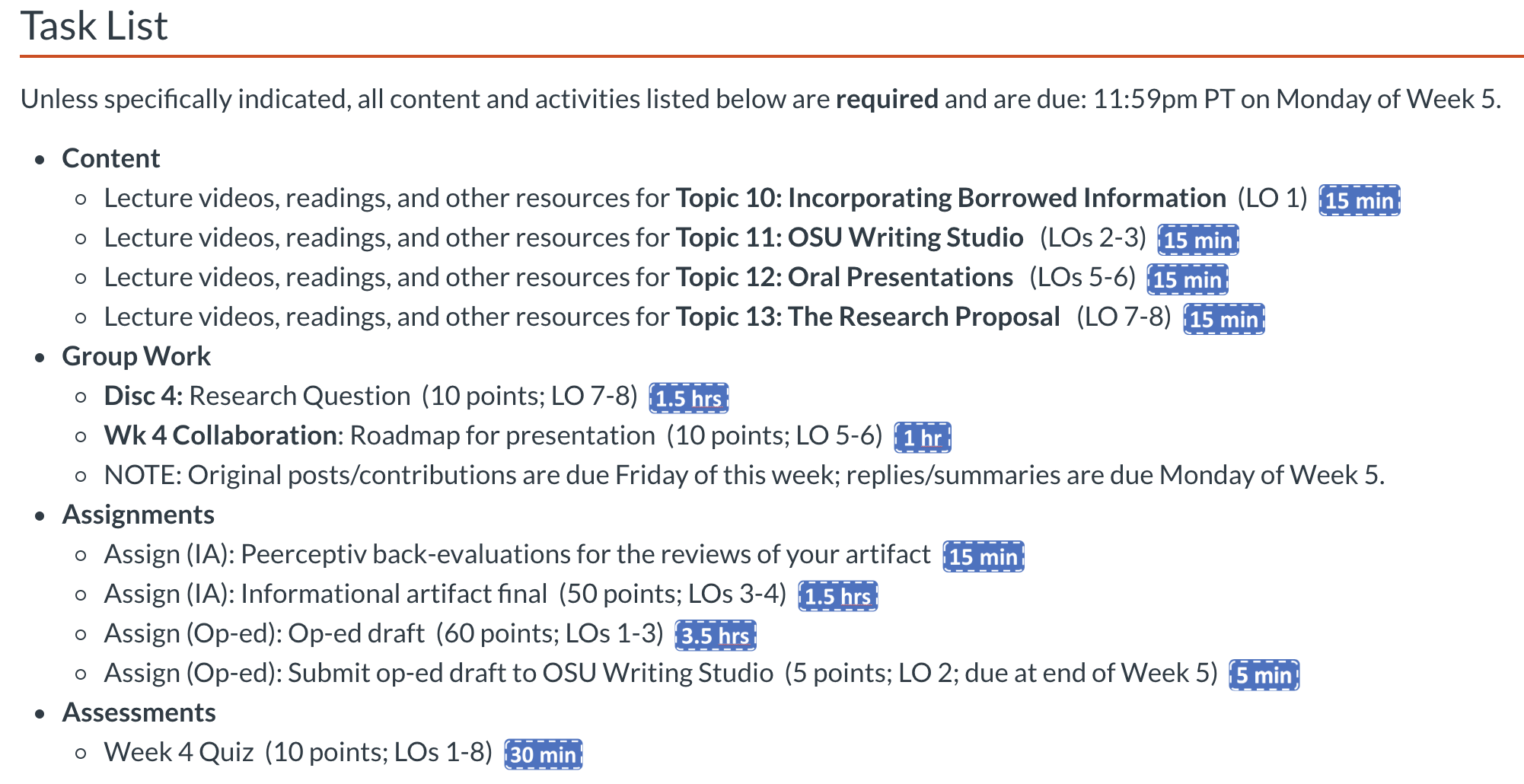

I personally use outlook calendar, google calendar, and word document to create my personalized study at the beginning of a new term. Rice University’s Center for Teaching Excellence provides an online tool for course workload estimation that is worth checking out. Read-O-Meter by Niram.org will estimate reading time for you if you copy and paste the text into text input window. In Canvas Learning Management System, to help students plan their total study time needed, instructors could help students visually and visibly notice time needed for study, by stating estimated time for each and all learning activities, such as estimated reading time, video length, estimated homework time, etc. The following is an example Dr. Meta Landys used in her BI 319 online course.

Image 1: Task Time Estimate and Visual Calendar of the Week in BI 319 “Critical Thinking and Communication In the Life Sciences” online with Instructor Dr. Meta Landys.

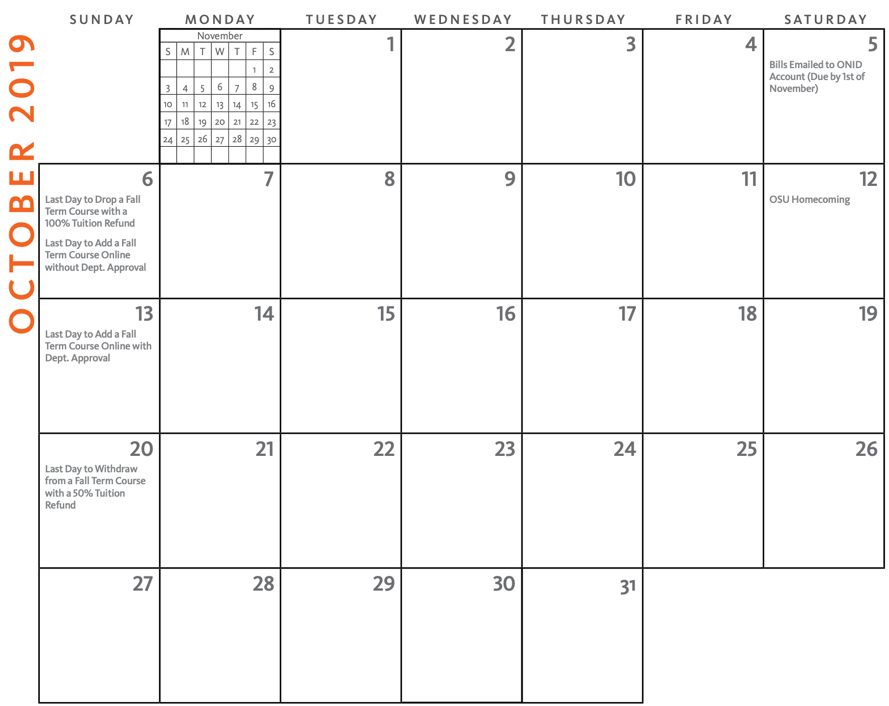

At program and institutional levels, keeping important dates visible to students will also help students stay on top of their schedule and not miss important timeline. At Oregon State University, a user-friendly calendar is created for parent and family of our student population, which includes important dates regarding academic success and fun campus events. For example, on the page for October 2019, the calendar shows October 6th as the last day to drop a fall term course with a 100% tuition refund, and the last day to add a fall term course online without departmental approval. These important dates could also be added to Canvas course modules or announcements, just as friendly reminders to students to make relevant decisions in time.

Image 2: Oregon State University Parent & Family Calendar with important dates such as last drop to drop a course with 100% tuition refund; first date to register for a course for the coming term, etc.

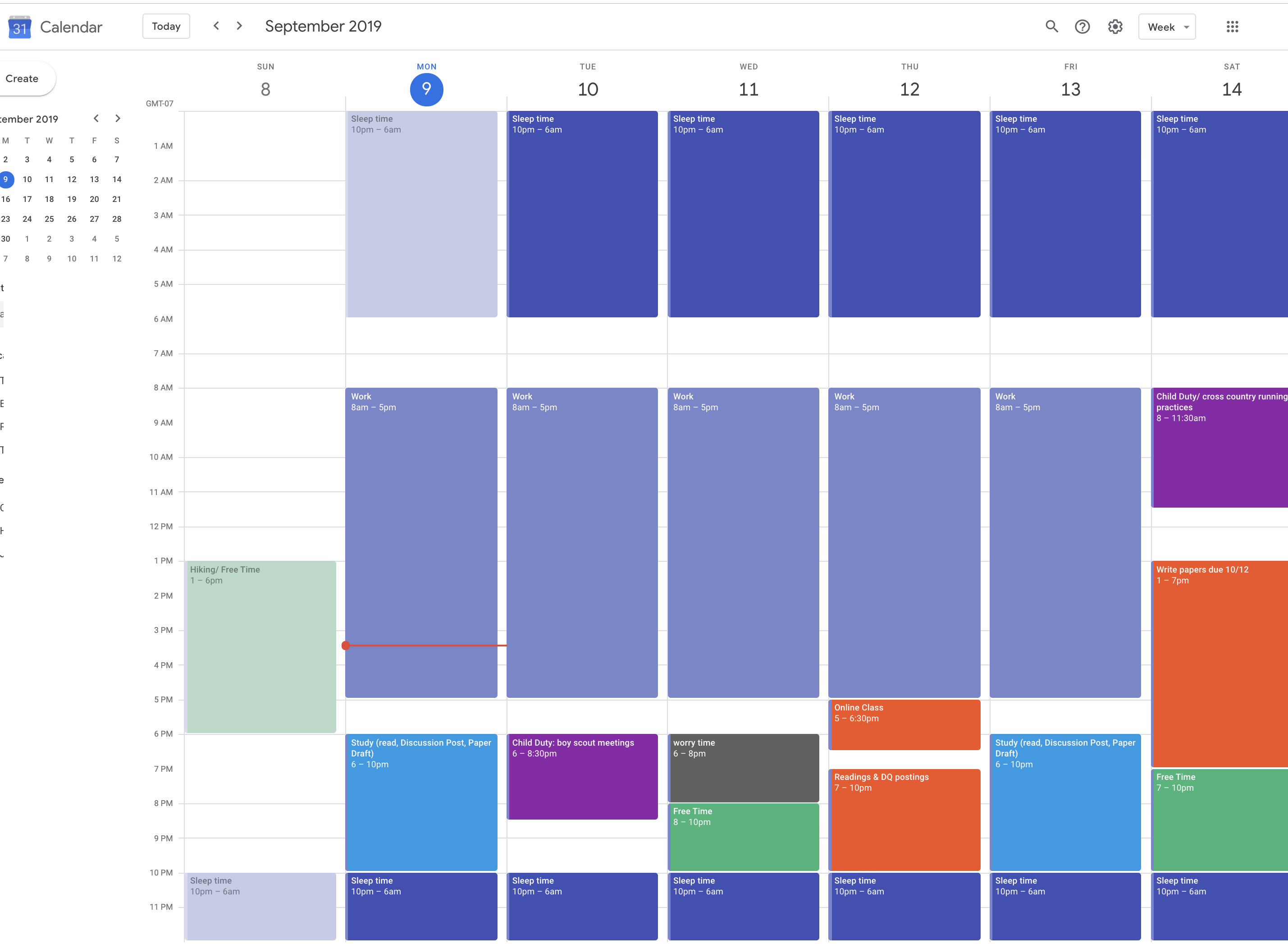

It is true that there are plenty of resources on time management for students to learn by themselves. However, not all students know how to manage their time, even with the aid of digital tools. The problem is that when students are not required to make a detailed schedule for themselves, most of them will choose not to do it. The other side of the problem is that there is very few activities which students are required to show instructors that they have planned/scheduled time for readings and all other study activities for the courses they are taking. In Canvas, to train students in time management skills, instructors could give an assignment in week 1 to have students plan their weekly learning tasks for each of the 11 weeks. Students can use a word document, excel spreadsheet, apps, or google calendar to plan their time. Charlotte Kent (2018) suggests asking students to include sleep time, eat time, commute time, worry time, and free time and four to eight hours of study time per week per course. Yes, scheduling worry time and free time is part of the time management success trick!

Image 3: A color-coded google calendar example of scheduling study time for a student taking two courses online while working full time and raising children.

To sum it up, there are many ways instructors can help students to develop time management skills, instead of assuming it is individual students’ responsibility to learn how to manage time. Instructors could make estimated study time for each learning activity in a module/week. Instructors could require students to plan study time for the entire term at the beginning of the course. And instructors could recommend students to use apps and tools to help them manage time as well! If you have other ways to help students manage time well, feel free to contact me and share them with us: Tianhong.shi@oregonstate.edu.

References

Collier, Sabrina. (2018). Best Time-Management Apps for Students. Top Universities Blog.

https://www.topuniversities.com/blog/best-time-management-apps-students

Fetzner, Marie. (2013). What Do Unsuccessful Online Students Want Us to

Know? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17(1), 13-27.

Kent, Charlotte. (2018). Teaching students to manage their time. Inside Higher Ed. September

18, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2018/09/18/how-teach-students-time-management-skills-opinion

Perez, M. (2019). September 2019 Oregon State University Ecampus Un-All-Staff meeting.

Oregon State University. (2019). Parent & Family Calendar 2019-2020. Retrieved from

https://families.oregonstate.edu/sites/families.oregonstate.edu/files/web_2019_nspfo_calendar.pdf

made with wordart.com

made with wordart.com (image generated at

(image generated at

(image from Canvas LMS Peer Review Tutorial on Peer Review)

(image from Canvas LMS Peer Review Tutorial on Peer Review)

Graphic expression – Assignment #1: Create a three-dimensional image

Graphic expression – Assignment #1: Create a three-dimensional image Audio/visual expression – Assignment #2: Create a video to explain what “reciprocal space” mean to you

Audio/visual expression – Assignment #2: Create a video to explain what “reciprocal space” mean to you Textual expression – Assignment #3 & #4: Literature search & Quizzes & Discussions & write a letter to a relative to explain why the Fourier transform is so important to NMR spectroscopy

Textual expression – Assignment #3 & #4: Literature search & Quizzes & Discussions & write a letter to a relative to explain why the Fourier transform is so important to NMR spectroscopy Textual expression of application – Application type of project: Personal Ethical Action Plan

Textual expression of application – Application type of project: Personal Ethical Action Plan