For the past couple weeks, I’ve been in Townsville, Australia, where I’m a guest of Dr. David Bourne at the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS). Between AIMS and the nearby James Cook University (JCU), the area is one of the world’s premier centers for marine and coral reef science, and it’s chock-full of the fields’ leading researchers. I’m here to meet them while continuing my own studies, and I’m excited for the opportunity!

If you squint really hard, you might be able to see me waving from Townsville. Map made with Google Maps Engine Pro, with more map details here

Before I get into the details of my research and this trip in particular, a little background would be useful.

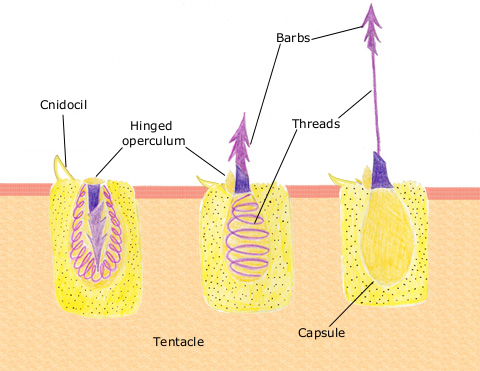

In my first post, I introduced the cnida, the sub-cellular harpoon mechanism that defines the animal group called Cnidaria. But cnidarians are interesting for a number of other reasons as well. For one thing, they’re beautiful, and extremely common in the ocean. From giant green anemones in the tidepools of the Pacific Northwest, to the beautiful corals and deadly Irukanji jellyfish in the waters of Australia, it’s hard to get in the water without noticing this diverse phylum of animals.

Giant green anemones (Anthopleura xanthogrammica) fill the tidepools of my beloved home state of Oregon

They are also ecosystem engineers. That is, species such as corals are the irreplaceable foundation that supports all the other species in their habitat. Without corals, there would be much less physical structure in the areas now occupied by reefs. Less structure leads to less diversity, and less diversity is both boring and bad for people, who rely on reefs for food, tourism, storm protection, drug discovery, and more. Further, without thousands of years of coral growth, many islands would have completely sunk under the sea.

Living corals have have produced all of the slopes, ledges, cracks, and crevices that create a diverse environment on this French Polynesian reef

In addition, cnidarians have a strange and unique biology. Among other things, many cnidarians form an essential partnership with single-celled algae called Symbiodinium. In this partnership, algae are kept inside the cells of the cnidarian, where they use photosynthesis to store light energy in sugars that are shared with their host. In return for sugars, the cnidarian shelters its algae and provides it with the building blocks of proteins.

As wonderful as cnidarians are, some of them are in trouble. The corals that create some of the most diverse and beautiful habitats in the world are being wiped out by disease, predation, rising sea temperatures, and human activity. Although we understand some of the causes of coral loss, there are still many that we don’t. After years of study, we have still not identified the pathogens responsible for many important coral diseases, and we still don’t know exactly why they appear to have become so devastating only recently. In this context, our lab asks many questions in the field of coral microbiology, such as:

- Which microbes are responsible for disease outbreaks, and which are mostly harmless?

- Do rising ocean temperatures make corals more sensitive to pathogens?

- How are pathogens transmitted? Via sediment or water? Or through vectors such as algae, sponges, and corallivores, like parrotfish?

- What happens to the coral microbiome if the reef ecosystem is transformed by overfishing or increased agricultural runoff? Can the community recover from any harmful changes?

- How do various members of the microbiome interact with one another and with their hosts?

One of our studies in the Florida Keys investigates how direct contact with algae influences the coral mucus microbiome

Many of our projects focus on pathogenic viruses and bacteria, but the microbiome is even more interesting to me from a different perspective. I want to search for the microbes that are good for their hosts. With that information, our descriptions of stressor-induced microbiome shifts become even more useful. Fieldwork to begin a more detailed description of the ‘normal’ coral microbiota is thus one of the primary purposes of my visit to Australia. For a few more details, check out this page and come back for more later. And don’t hesitate to ask questions!!

My current trip is funded by the East Asia and Pacific Summer Institutes (EAPSI) program; a collaborative effort between the United States’ National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Australian Academy of Science (AAS). Since I’ve arrived in the country, I’ve had some time to explore a bit, and was hosted for an orientation session by AAS in the capital city of Canberra. In a couple weeks, I’ll be traveling to Lizard Island Research Station, and I expect to get some great photos while there. For more details on the people I’ve met and the fun stuff I’ve seen and learned, come back soon.