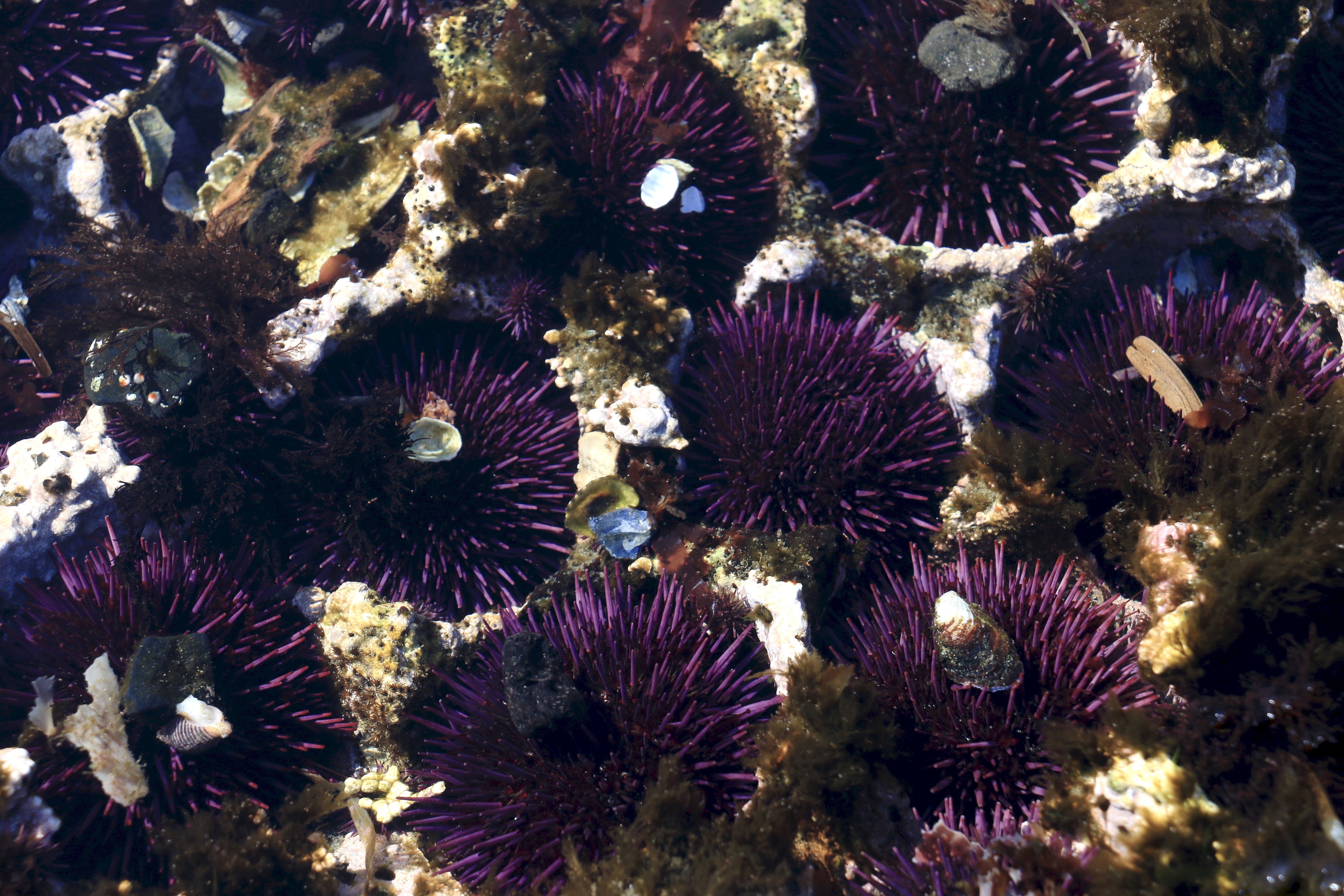

This week marks the 10 year anniversary of Oregon’s decision to pilot a system of marine reserves. On July 28, 2009, Gov. Kulongoski signed HB 30131, which directed the implementation of two pilot marine reserves at Redfish Rocks and Otter Rock. The bill also directed study of additional marine reserves using a community process, and as a result of this process, three additional marine reserves (Cape Falcon, Cascade Head, and Cape Perpetua) were designated during the 2012 legislative session. Oregon’s current system includes five no-take marine reserves (40 mi2) and nine adjacent marine protected areas (~77 mi2), an area that totals roughly 10% of Oregon’s Territorial Sea.

Ten years – the merest of moments geologically speaking, but a (somewhat) long time from a human point of view. Because 10-year anniversaries are often a time of reflection, let’s take this time to look back on all the sweet (and less than sweet) memories of Oregon’s relationship with the concept of marine reserves. The impetus for my reflection came from the fact that although my current duties are about looking forward, as Carl Sagan said, “You have to know the past to understand the present.” So, I have certainly spent some time trying to better understand the policy landscape surrounding this issue. I have been assisting the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee as they prepare to submit a legislatively-mandated report to Oregon’s Legislative Assembly regarding the status of Oregon’s Marine Reserves in 2023; this report is to include “an assessment of social, economic and environmental factors related to reserves and protected areas” as well as “recommendations for administrative actions and legislative proposals related to the reserves and protected areas.”2 The report is to be prepared by an Oregon university, but making things a bit more complicated is that no funding was allocated in the bill for this assessment process.

But before we continue, we should get on the same page about terminology. Marine protected areas are defined as, “…any area of the marine environment that has been reserved by federal, state, territorial, tribal, or local laws or regulations to provide lasting protection for part or all of the natural and cultural resources therein.”3 Marine protected areas can allow many extractive uses with few protections or they may allow very little extraction with limited exceptions (for example, recreational harvest of certain species). Marine reserves are a special class of marine protected areas, where no extraction of living or non-living resources is allowed with the exception of take for scientific research. Marine reserves around the world have been established for different purposes, but the purpose of Oregon’s Marine Reserves is to “provide an additional tool to help protect, sustain or restore the nearshore marine ecosystem, its habitats, and species for the values they represent to present and future generations.” 4

Oregon’s foray into using marine reserves as a management tool began about 20 years ago; in 2000, Gov. Kitzhaber’s office requested that Oregon Ocean Policy Advisory Council (OPAC) begin gathering information regarding marine reserves as a management tool. Over the next two years OPAC organized informational meetings with experts and regional natural resource managers, held public meetings with Oregon ocean stakeholders, and collected written comments, which typically landed on one of two opposite ends – very supportive or very opposed. In its 2002 Report and Recommendations to the Governor, OPAC recommended that Oregon should test a limited number of marine reserves, and that those reserves should be determined based on “…an open, public process with extensive stakeholder involvement.”5 The discussions and resulting report set off a contentious debate between industry, conservation groups, and the state government, ultimately postponing what was to come by about a decade. Industry groups and fishing communities voiced concerns that such designations would cause further economic harm to Oregon’s coastal communities, which were still reeling from the groundfish disaster and salmon crises of the 1990s. Various government entities and environmental groups indicated that such measures were needed to help avert such disasters in the future.

What changed in the intervening decade? Sentiment-wise, not a lot as far as I can tell. Staunch advocates remained staunch advocates and vocal opponents remained vocal opponents but political winds were shifting. A number of major reports, the work of national and international scientific experts, sounded the alarm in no uncertain terms that human activities were causing major and detrimental impacts to ocean ecosystems and thus human well-being 6–8. Increasing interest in wave energy development raised a new set of concerns for the fishing industry and fishing communities.

And so, in 2005, Governor Kulongoski requested that OPAC re-visit marine reserves. OPAC’s Marine Reserves Working Group met several times over the next couple of years and in 2008, Executive Order 08-07 accelerated the marine reserves process in Oregon. In line with the process for extensive stakeholder involvement in siting and planning outlined in EO 08-07, community groups and citizens submitted 20 proposals, and on November 29, 2008, OPAC forwarded its recommendation on pilot sites and sites for further consideration to the Governor’s Office. The following November, after passage of HB 3013 (the legislation that established the pilot marine reserves), ODFW’s newly-established Marine Reserves Program worked with OPAC to form community teams to study the sites recommended for further evaluation. With the aid of a facilitator the community teams worked diligently over the next year, logging a total of 35 meetings and ~25,000 collective volunteer hours over an 11-month period to develop their final recommendations, which were submitted to the legislature in early 2011. Although legislation was introduced during the 2011 legislative session to establish the three new sites, negotiations were unsuccessful and the bill died in committee. Between the 2011 and 2012 sessions, the Coastal Caucus (the bipartisan, bicameral group of legislators representing coastal districts) worked to craft a plan that would receive support moving forward. On March 5, 2012, Gov. Kitzhaber signed SB 1510 and the period of marine reserves planning gave way to implementation.

One of the major concerns among opponents during the contentious first decade of marine reserve discussions was that we don’t understand enough about using marine reserves as a management tool. A common theme among proponents was that we can’t wait until we know all the answers and that science should help guide an adaptive management process.

So what have we learned? A quick Web of Science search reveals that since 2000, over 2000 peer-reviewed articles regarding marine reserves globally have been published, with >100 new papers every year since 2008. Change the topic search term to “marine protected areas” and the number of publications is more than doubled. The oldest marine reserves and protected areas are now decades old, and many publications in recent years have synthesized this wealth of data to examine the effectiveness of marine reserves, both from an ecological and a human well-being standpoint.

And as far as Oregon’s nearshore is concerned, the ODFW Marine Reserves Program’s research collaborations and monitoring efforts have contributed new understanding about Oregon’s notoriously difficult-to-study waters (I encourage you to visit the Reserves News to learn more about the research happening in the reserves). While the Marine Reserves Program’s eyes are on the ocean, the eyes of the nation will be on Oregon as the process unfolds. Nationally, Oregon has a reputation as a conservation leader and also a leader in collaborative governance processes that involve citizens in important land use and coastal management decisions – often referred to as “the Oregon Way.” Such participatory processes don’t usually make any one group happy, but they do have the ability to ensure that people feel heard. And when people feel that they had a place at the table, efforts are more likely to succeed.

What is the future of Oregon’s marine reserves system? One of the points of the mandated assessment is to provide valuable information to Oregon’s ocean stakeholders so that adaptive management as envisioned in OPAC’s 2008 Marine Reserve Policy Recommendations can take place. As the 2023 assessment nears, it is time to start thinking about this important next step. Given the current political climate and the still-raw emotions from the 2019 legislative session, it’s helpful to reflect on the fact that Oregonians can have difficult discussions, make tough compromises, and move forward together.

References

1. House Bill 3013. Relating to ocean resources; and declaring an emergency. (2009).

2. Senate Bill 1510: Relating to ocean resources; creating new provisions; amending ORS 196.540; and declaring an emergency. (2012).

3. NOAA Marine Protected Areas Center. Definition and Classification System for US Marine Protected Areas.

4. Ocean Policy Advisory Council. Oregon Marine Reserve Policy Recommendations: A Report to the Governor, State Agencies and Local Governments from OPAC. (2008).

5. Ocean Policy Advisory Council. Report and Recommendation to the Governor: Oregon and Marine Reserves. (2002).

6. Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. (Island Press, 2005).

7. Pew Oceans Commission. America’s living oceans: charting a course for sea change. A report to the nation. (Pew Trusts, 2003).

8. US Commission on Ocean Policy. An ocean blueprint for the 21st century. (US Commission on Ocean Policy, 2004).