I’m going to play Nature’s advocate for a moment. Let’s be honest, many of us are bombarded with constant reminders to unconsciously check our phone or computer on a daily basis. It’s easy to become tied to an electronic device without realizing. For Smartphone users, the convenience of having our entire agenda and communication network stored electronically means that we’re checking our phones from the moment we wake up. Whether it’s the stream of emails, demanding social media notifications or a missed message from friends and family, there is no doubt all the time spent on electronics can have some effect on our mental health.

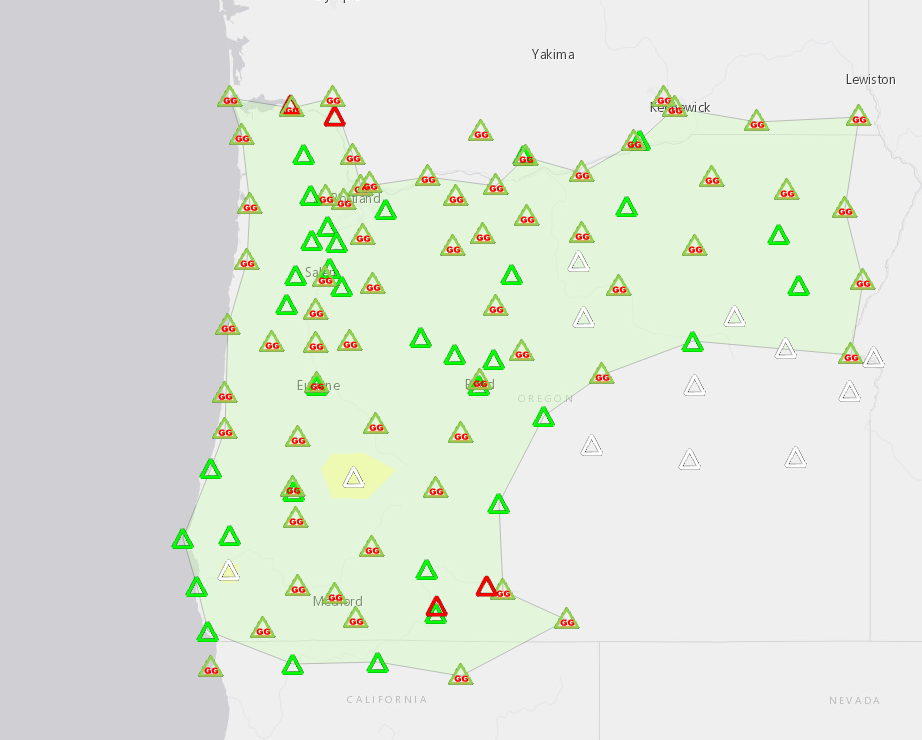

The most extensive study to date estimates that people across all age groups in the United States check their phone on average 46 times per day, which totals to upwards of 8 billion times a day that all Americans are collectively checking their phones. It has been suggested that as a society, Americans have become so accustomed to daily “screen time” at a young age, that they are getting significantly less “green time.” Only 10 percent of teens in America spend time outside every day, according to a recent Nature Conservancy survey. The documentary film, Play Again, also explores the decrease in “green time” and increase in “screen time” through the case of seven teenagers from Portland, Oregon. Despite being surrounded by ample opportunity to explore outdoors, these young Oregonians exemplify the troubling estimations of American youth spending an average of 7-½ hours per day in front of a screen. As I alluded to in my earlier blog post, the more connection we have to the natural world around us, the more likely we will care enough to conserve it, but have we lost that crucial connection by spending less time outdoors?

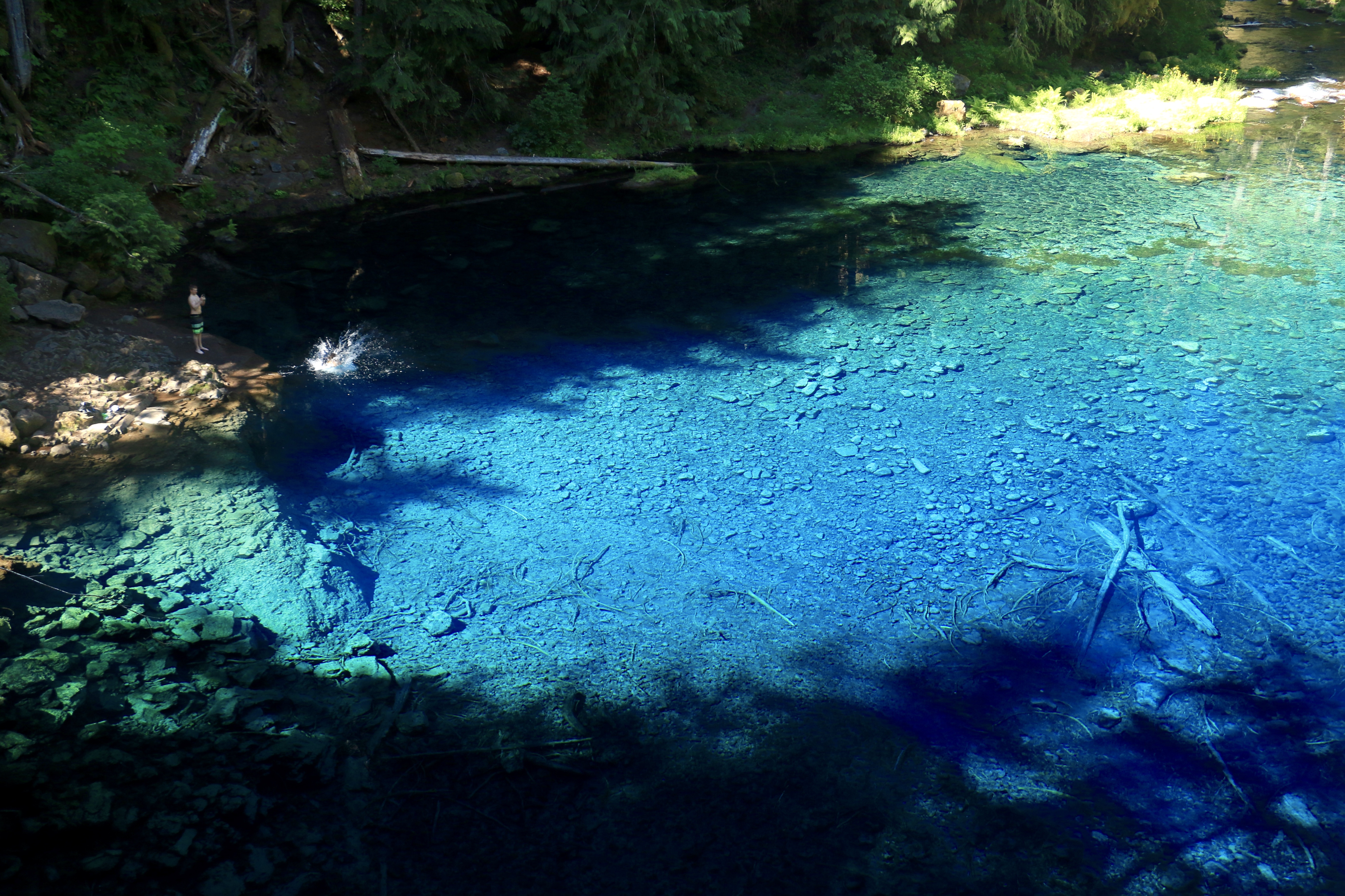

Spending green time on a hiking trail in Willamette National Forest.

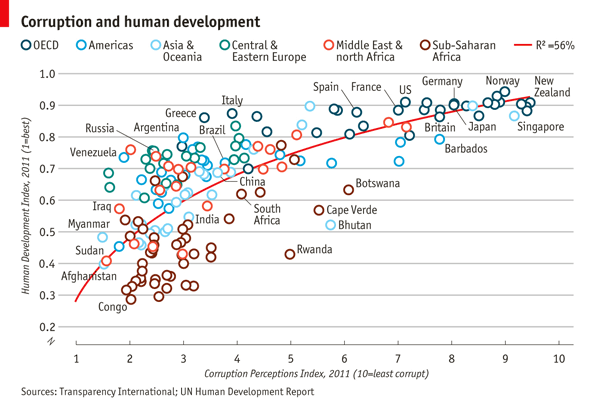

On a related note, surveys often reveal a good bit of insight into a larger question or issue, which can help inform where changes need to be made. That is exactly the focus of my work at the moment, as I have tirelessly been drafting and rewriting an ocean literacy survey to assess the knowledge of the general public who visits the coast of Oregon. One of the things that struck my curiosity as I wrote and rewrote this survey in collaboration with the ODFW Marine Reserves team has been where individuals receive their information about ocean-related issues. I am interested to find if there is some sort of link between the sources of media where individuals receive information and the gap in knowledge relating to ocean health threats.

I’ll admit, it’s a bit ironic and probably hypocritical for me to play nature’s advocate after spending several full workweeks indoors on a computer, but I took advantage of a three-day weekend off work to ensure that I refreshed my mind in the outdoors. And let me tell you, it worked.

“Immersing” in nature at Tamolitch Blue Pool

Dr. David Strayer, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Utah argues that after three days of wilderness backpacking, our brains perform significantly better on creative problem solving tasks. He calls this the three-day effect, where immersing oneself in nature for long enough can clean one’s “mental windshield” that becomes clouded over from the stress of being indoors. Other studies have shown that it doesn’t take that much to recharge our cognitive function, as just 25 minutes of “green time” can give our brain the rest it needs from “screen time.”

Gazing into the Milky Way from my tent at Blue River Reservoir.

As a frequent saying goes, “there is no wifi in the woods, but I promise you’ll find a better connection.” Driving through Willamette National Forest this weekend, I realized it would have been nice to have service while searching for a campsite, but instead I had to problem solve on my own. With my phone switched off and stowed away, I managed to find an ideal campsite and spent the night losing track of time while gazing at the countless stars. And let me tell you, waking up to the sound of birds chirping and the sunlight penetrating through the trees into your tent feels much more refreshing than the harsh sound of an alarm clock in a dark bedroom. Many others must have received the “green time” memo as well, as all of Willamette was flooded with campers, hikers and outdoor enthusiasts alike. Bearing in mind the statistics of recent “screen time” surveys, it’s a restoring feeling to see others catch up on their vitamin “N.”

Isn’t it awesome?!

Isn’t it awesome?!