This past week I worked with Dr. DeBano on Monday and Tuesday at Starkey. I worked on pan traps and timed handnetting while Dr. DeBano worked on collecting data relating to plant richness, blue vein traps (BVT), densiometer, and solar pathfinder. We then began cleaning up all the whiskers and flagging at each site, as she will not be returning to Meadow Creek next year. I’m also officially done with all the field work, but I will be continuing to work on data entry and quality control. As all of the data has been collected, it must now be organized and analyzed. After that Dr. DeBano will work on completing three separate research papers to showcase all the work that’s been conducted over the last several years.

Since this is also my last blog post, I thought I should do a quick explanation of how each of the different projects influence each other and work towards the overall goal of seeing how agriculture and grazing affect native bee populations on the Zumwalt and within Starkey. Honestly, I’m as nervous for this blog post as I was for my first one. Mainly, I hope to give a solid, streamlined, explanation of the project. But it’s also hard to convey just how hard Dr. DeBano and her team have worked on this project. It has been a massive undertaking, and I’ve watched her sacrifice personal time in exchange for long nights in the field or her office. But through it all, Dr. DeBano has stayed passionate. For example, it was refreshing to see her still get giddy over a pair of bumble bees gorging on thistle. She truly seems to have a love for knowledge, sharing, and research. While I don’t know what my own career path holds, I hope that I’ll have as much enthusiasm as she does for her work.

Starkey

I only spent about four days at Starkey, so I’ll do my best on this part! Dr. DeBano has been collecting data for this project from the Starkey Experimental Forest for several years (since 2016 I believe). During that time she has worked within the Meadow Creek area, and has been collecting bees and conducting plant surveys from 3 separate pastures within that area. The pastures are Star 2, Star 3, and Star 5. Within each pasture there are 4 different sites: All, DE, LS, and None. The names come from what is included, or excluded, from each site. For example, the All sites are open to all animals such as deer, elk, cattle, and whatever else roams into the area. While the DE sites are only open to deer and elk, LS is only for cattle, and None sites excludes all animals. Dr. DeBano said that cattle were only introduced to the sites in 2016.

To see what bee species inhabit the pastures Dr. DeBano uses pan traps, BVTs, and hand netting to collect specimens. BVTs are similar to pan traps, except the trap is one large yellow and blue trap that sits a few feet off the ground, whereas there were three pan traps set on the ground around each transect’s backbone The BVT is placed within the center of the designated transects. There is some controversy to the technique, as some scientists argue that its elevated height attracts bees from outside the research area. Dr. DeBano stated that she also hopes to compare the difference between BVTs and pan traps, and see if there actually was in variance in species. To see what flowers are blooming and available to pollinators, Dr. DeBano collects data on species richness and additionally goes along each line of the transect and counts how many of each blooming plant is present during the given time. The densiometer and solar pathfinder help record canopy cover and how much daylight is present on a given day.

There has also been a lot of riparian restoration work conducted within Meadow Creek, and so our sites are shared with a few other research projects. One of the projects is studying what grazes on willows, and which willow species thrive. Researchers at Starkey are also looking at how deer and cattle interact within the forest. But for Dr. DeBano’s project she is exploring how native bees are altered by herbivory. She wants to see what drives the bee communities and how agriculture influences their populations. By looking at what bees and forbs exist at the differing sites gives a better insight into what species are present. For example, there may be double the amount of bees and plants present at the None sites verses the LS sites. Additionally, the cattle or deer and elk may be grazing on plants at a site that would otherwise support specific bees. She also records this data from April to September, and is then able to get a better idea of when various plants are blooming.

Zumwalt

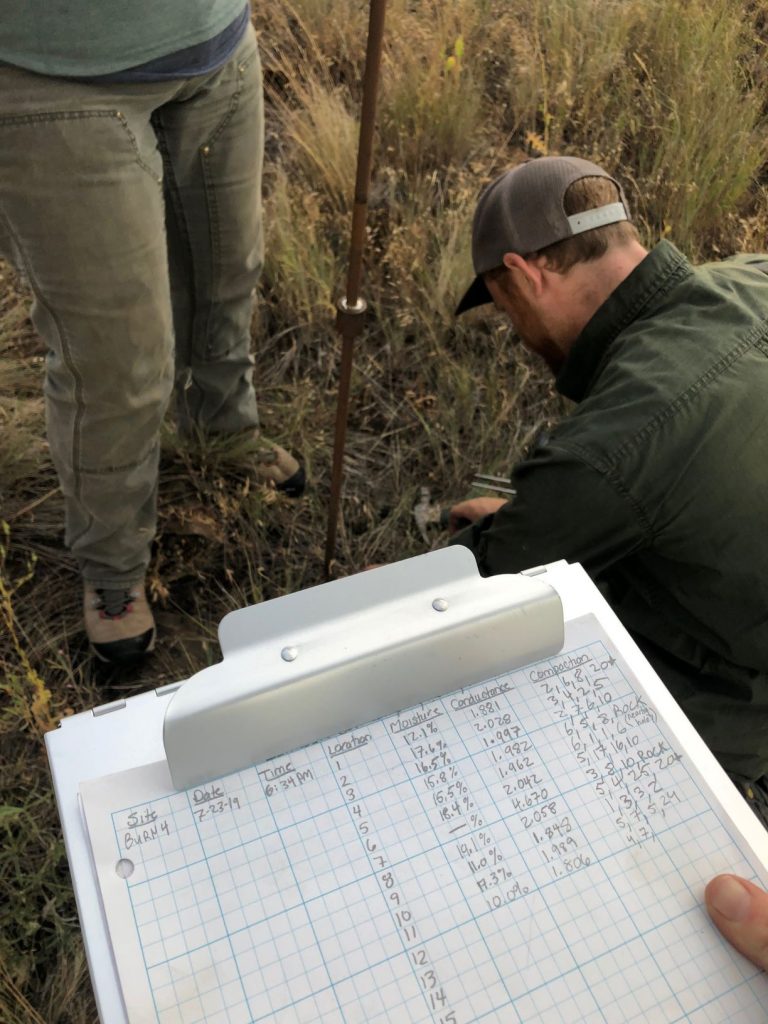

There are a few similarities and differences to the work being conducted on the Zumwalt that should be noted. For instance, we never used BVTs, densiometers, or solar pathfinders, but more work was done in regards to soil compaction, ground nesting bees, and ground cover. Dr. Morris also conducted a lot of research on non-native grasses and the effects of fire on grasslands. There are also 30 sites at the Zumwalt (as opposed to the 12 at Starkey), and they range from: grazed, burned, native prairie, old fields, or both. As for similarities, bees were also collected with hand netting and pant traps. Plant richness and blooming plant surveys were also conducted in the same fashion as Starkey.

Dr. DeBano is looking at how agriculture alters bee communities within the prairie. Because the prairie was historically cultivated, Dr. DeBano is able to look at how those sites compared to native fields. The cultivated fields have been left in passive restoration for several decades now, but the differences in plant communities is still visible from across the preserve. For instance, the cultivated fields seemed to be full of more non-native grasses, and supported a smaller variety of forbs.

Bees

As for the bee species, all of the bees are sorted and pinned, and then shipped to a taxonomist in Utah. And Katie’s thesis focuses on meta barcoding of bees that were hand netted in the field. The data will be able to tell her exactly what flowers are within the pollen collected from the various bees. This will give them a better idea of what flowers each bee species takes advantage of. This is exciting, new science, and I’m eager to know what the data reveals!

Because such little work has been done on the native bees in these communities, all of the data collected is beneficial. With this knowledge Dr. DeBano will be able to decipher how and if cattle and ungulates influence said bee communities. This work can be used to alter grazing practices and restoration projects. I was honored to be picked for this internship, and I’m so grateful Dr. DeBano let me explore a variety of different projects. I also think it was great that I got to come on during the end stages of collecting data. I got to see all of the labor that’s already been put into this project, and was able to learn about patterns they had already begun to see. Besides the obvious sensory joy of spending my summer surrounded by charismatic bees, beautiful flowers, and one of the most phenomenal prairies in the west, I also got to spend a few months around positive, motiving thinkers. I hope my blog gave this project the recognition it deserves, and I also hope it inspired somebody to look at our grasslands through a different lense.

This past week I went back to the Zumwalt to assist with more field work. I accompanied Katie for her last days of field work, in which we collected more bees with the hand nets. This week, however, proved to be a little more difficult than the first as much of the prairie had begun to turn brown. We also faced the challenge of high winds, storms, and grazing cattle at some of the sites. All these factors resulted in less bees, or at least less than favorable catching conditions. Regardless, it was still nice to be out in the field and take note of how the prairie was transitioning out of late spring to high summer.

This past week I went back to the Zumwalt to assist with more field work. I accompanied Katie for her last days of field work, in which we collected more bees with the hand nets. This week, however, proved to be a little more difficult than the first as much of the prairie had begun to turn brown. We also faced the challenge of high winds, storms, and grazing cattle at some of the sites. All these factors resulted in less bees, or at least less than favorable catching conditions. Regardless, it was still nice to be out in the field and take note of how the prairie was transitioning out of late spring to high summer. Our last site for the week proved to be the most fruitful though, we collected all the required specimens and then some in less time than it took to collect even a quarter of the amount at prior sites. Since this week was fairly similar to my first week on the prairie, I’ve decided to include a couple examples of the different forbs we frequently see on the Zumwalt. It’s been interesting to see the colors on Zumwalt shift from purple lupin and yellow cinquefoil to mostly white yarrow and pink fairy in such a short amount of time. I will continue to showcase a few each week, and will keep it simple by including the scientific name, family, common name and photograph. This next week I will be back in Hermiston pinning many more bees and assisting with data sheets. And, as an added bonus I added two beautiful insects that Jame’s found while hand netting.

Our last site for the week proved to be the most fruitful though, we collected all the required specimens and then some in less time than it took to collect even a quarter of the amount at prior sites. Since this week was fairly similar to my first week on the prairie, I’ve decided to include a couple examples of the different forbs we frequently see on the Zumwalt. It’s been interesting to see the colors on Zumwalt shift from purple lupin and yellow cinquefoil to mostly white yarrow and pink fairy in such a short amount of time. I will continue to showcase a few each week, and will keep it simple by including the scientific name, family, common name and photograph. This next week I will be back in Hermiston pinning many more bees and assisting with data sheets. And, as an added bonus I added two beautiful insects that Jame’s found while hand netting.