This past week I stayed on the Zumwalt with Scott and Kaylee to work on soil sampling. And let me just say, we had quite a roller coaster ride. We left La Grande around 9AM on Tuesday and arrived at Summer Camp sometime before noon. We stopped at camp to unload all of our gear before heading out to the field sites, and it was then that I noticed we had a flat of all flats. We, mostly Scott, then worked on putting the spare on during the heat of the day. After we got the Suburban back in working order we all agreed it would be best to drive back to Enterprise and get the old tire patched up. The Zumwalt is comprised of dirt roads for miles and is full of notoriously bad pot holes, jagged rocks, and rivets. In addition, we frequently traverse the Salt Road, which is more of a riveted trail than a road that’s only driven during the field season. As such, we decided we didn’t want to get an additional flat tire deeper into the preserve. So, we drove to the closest Les Schwabb and Scott called Dr. DeBano. She then decided we should get all new tires and an alignment. We then walked around bustling Enterprise, and stopped at a local restaurant while we waited for the mechanics to finish.

When we finally got back to the prairie we decided to get at least one site completed. Somebody way up above must have felt our frustration because we then got to see one of the most glorious sunsets I’ve seen (and I’m a Florida native). A large storm began rolling in, and I’m sure we all thought the universe was going to continue its gruel joke and rain on us. But instead, the storm broke apart and then the entire Zumwalt was bathed in warm orange light while sunbeams showered the hills. The dark blue clouds contrasted with the warm grass. Eventually, the orange sky turned purple and magenta on the horizon and eventually a cool blue overtook the prairie. The Seven Devil Mountains then emerged from a storm and the bright rock contrasted perfectly against the dark storm clouds. All the while we were working next to a Graze site, so I got to admire the most picturesque cattle. After we completed the sampling we decided to go up to Monument to get a better view. Monument are two large man made cairns. TNC speculates that they were made by ranchers generations ago as a directional marker. As such, you can see Monument from most of the prairie, and vice versa. Later that night we all sat outside to star gaze. The cross in the Milky Way was visible, and it was nice to watch for shooting stars. While cliche, feeling so small is always grounding.

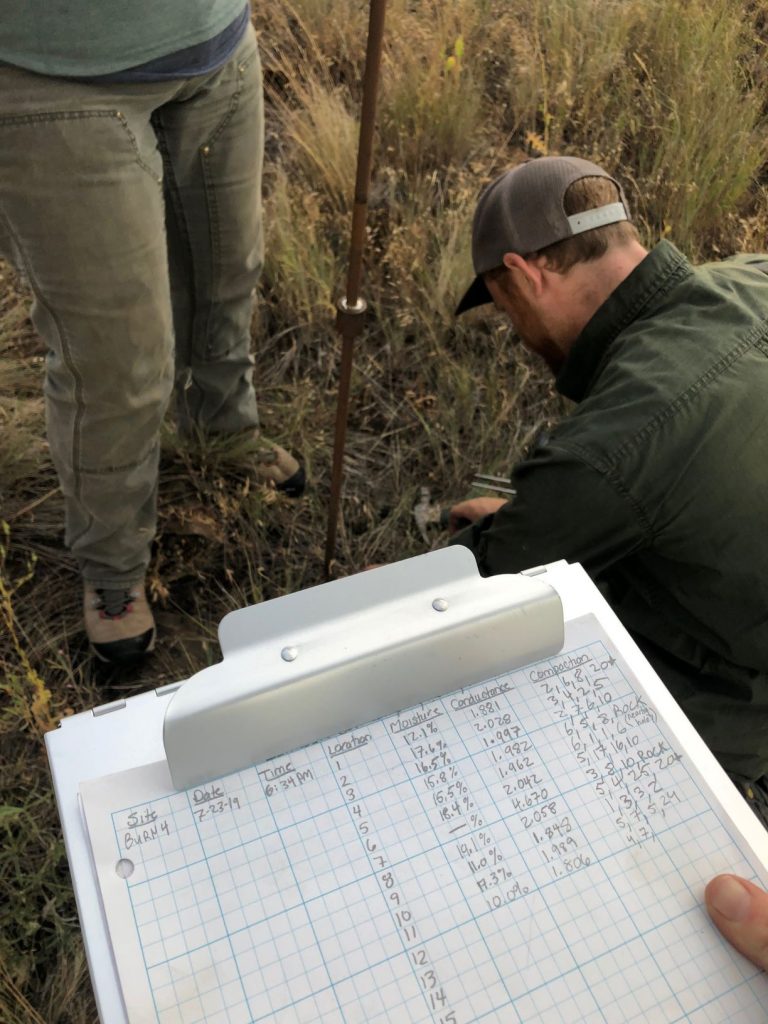

The next day we got up early and hit the ground running around 7:30 AM. Our goal was to complete soil sampling at about 20 sites for the week. The only tools we took out were a HydroSense II and a Penetrometer. The HydroSense II looks more like a stud finder with two metal prongs attached. You stick it into the ground and it then reads back the VMC, volumetric water content percentage, and conduction. The Penetrometer is a large metal pole with a 5-10lb weight that you slam into the ground. The bottom on the pole has 4 markings on it that indicate 5cm increments. You drop the weight and count how many times it takes to go 5 cms, culminating in a 20cm reading. The point of the task is to record how compact the soil is, so the most strikes it takes the more compact the soil. Our guide tool for the HydroSense II broke at the first site, so we all agreed that Scott would be in charge of the readings for the remaining sites. Since the reader is an extremely expensive piece of equipment we didn’t want to be responsible for its downfall. As such to break up the task Kaylee and I took turns between tampering the soil and being a scribe. Of course, I ended up getting my finger caught between the metal and sliced my finger open. After a few explicitis were yelled I got bandged up and went back to work.

The data collected will be used to compare soil characteristics between sites. For instance, it seemed like the old fields were rockier and more compact than native fields. It is speculated that this is because these fields were once cultivated and have had no restoration efforts. Scott said that he thinks those sites haven’t been plowed since the 1950s, which makes it’s impressive that the soil is still so compact after 70 years. Prairies and deserts are notoriously unforgiving when it comes to soil disturbance, so I wasn’t especially surprised. In parts of Oregon you can still see sheep trails in the hills from decades ago. We also didn’t see much rhyme or reason to the moisture content and conduction though. For instance, we would get a reading of around 7% and then 13 feet down the transect would get 30%. We did take all of our readings on the transects that are used for pan traps and frequency data. We made sure to be within a meter of the markers, but not directly on them. Since people frequent those transects it might create biased data if you take readings directly on the whiskers.

On our last day we ended up near Duckett Barn. There is a field of veetch near the barn, and I have never seen so many bumble bees! We stopped for about 10 to 15 minutes and just admired them, and snapped photographs of the charismatic insects. While it was bittersweet to see a nonnative plant creep into the prairie, it was fascinating to watch all the bees. My personal highlight, however, happened on our way out of the preserve. As we were driving we saw a badger cross the road! I’m pretty sure I started smacking Kaylee and talking gibberish. The badger then crossed the road and started bounding through the next field. We see badger holes all over the Zumwalt, but I have yet to see one in the wild. I was as elated as I was when I saw the wolf. I’m so grateful I get to work with Dr. DeBano on pollinators, but I seem to lose total control when it comes to Mustelids and Sciuridaes. A career goal of mine is to work with Black Footed Ferrets. But first, I need to perfect my volume control.

Despite the flat tire, smashed finger, and sore ankles I feel like we had a very productive week. Considering the setbacks I’m impressed we still completed 21 sites. We will be going back to the Zumwalt next week to finish our soil work. Dr. DeBano will also be joining us so we might assist with her data as well. I’m becoming more familiar with the layout of the prairie, and it’s fun to see it transition each trip. The awe of the Zumwalt has yet to warn off of me. I’ve worked a variety of jobs, but I suspect that this internship will feel special for a long while.

This past week I went back to the Zumwalt to assist with more field work. I accompanied Katie for her last days of field work, in which we collected more bees with the hand nets. This week, however, proved to be a little more difficult than the first as much of the prairie had begun to turn brown. We also faced the challenge of high winds, storms, and grazing cattle at some of the sites. All these factors resulted in less bees, or at least less than favorable catching conditions. Regardless, it was still nice to be out in the field and take note of how the prairie was transitioning out of late spring to high summer.

This past week I went back to the Zumwalt to assist with more field work. I accompanied Katie for her last days of field work, in which we collected more bees with the hand nets. This week, however, proved to be a little more difficult than the first as much of the prairie had begun to turn brown. We also faced the challenge of high winds, storms, and grazing cattle at some of the sites. All these factors resulted in less bees, or at least less than favorable catching conditions. Regardless, it was still nice to be out in the field and take note of how the prairie was transitioning out of late spring to high summer. Our last site for the week proved to be the most fruitful though, we collected all the required specimens and then some in less time than it took to collect even a quarter of the amount at prior sites. Since this week was fairly similar to my first week on the prairie, I’ve decided to include a couple examples of the different forbs we frequently see on the Zumwalt. It’s been interesting to see the colors on Zumwalt shift from purple lupin and yellow cinquefoil to mostly white yarrow and pink fairy in such a short amount of time. I will continue to showcase a few each week, and will keep it simple by including the scientific name, family, common name and photograph. This next week I will be back in Hermiston pinning many more bees and assisting with data sheets. And, as an added bonus I added two beautiful insects that Jame’s found while hand netting.

Our last site for the week proved to be the most fruitful though, we collected all the required specimens and then some in less time than it took to collect even a quarter of the amount at prior sites. Since this week was fairly similar to my first week on the prairie, I’ve decided to include a couple examples of the different forbs we frequently see on the Zumwalt. It’s been interesting to see the colors on Zumwalt shift from purple lupin and yellow cinquefoil to mostly white yarrow and pink fairy in such a short amount of time. I will continue to showcase a few each week, and will keep it simple by including the scientific name, family, common name and photograph. This next week I will be back in Hermiston pinning many more bees and assisting with data sheets. And, as an added bonus I added two beautiful insects that Jame’s found while hand netting.

My first week was spent on the Zumwalt Prairie. The Zumwalt Prairie is the largest remaining bunchgrass prairie in North America, and as such provides important habitat for various insects, birds, ungulates, smaller mammals such as ground squirrels and badgers, and more recently wolves. The Zumwalt sits at about 2,000 to 5,500 feet and is bordered by the Imnaha River and Hells Canyon, with the Wallowa Mountains and Seven Devils to the East. The prairie was historically used by the Nez Perce, and was then used for various grazing operations. The Nature Conservancy (TNC)eventually purchased 33,000 acres of the prairie, creating the largest private preserve in Oregon. Today, TNC works in conjunction with local ranchers to implement sustainable agriculture. The preserve also attracts hunters, birders, and prairie enthusiasts; as the Zumwalt is a mosaic of wildflowers in the spring and early summer. The preserve also has several historic buildings, including three that were transported to what is referred to as Summer Camp. In addition to a large barn, Summer Camp is comprised of the School House, Doctor’s Cabin, and the Bunk House, which are used to house employees and researchers. There are also pre established sites throughout the prairie that have been used for various research projects ranging from: soil, pollinators, biomass, and invasive species.

My first week was spent on the Zumwalt Prairie. The Zumwalt Prairie is the largest remaining bunchgrass prairie in North America, and as such provides important habitat for various insects, birds, ungulates, smaller mammals such as ground squirrels and badgers, and more recently wolves. The Zumwalt sits at about 2,000 to 5,500 feet and is bordered by the Imnaha River and Hells Canyon, with the Wallowa Mountains and Seven Devils to the East. The prairie was historically used by the Nez Perce, and was then used for various grazing operations. The Nature Conservancy (TNC)eventually purchased 33,000 acres of the prairie, creating the largest private preserve in Oregon. Today, TNC works in conjunction with local ranchers to implement sustainable agriculture. The preserve also attracts hunters, birders, and prairie enthusiasts; as the Zumwalt is a mosaic of wildflowers in the spring and early summer. The preserve also has several historic buildings, including three that were transported to what is referred to as Summer Camp. In addition to a large barn, Summer Camp is comprised of the School House, Doctor’s Cabin, and the Bunk House, which are used to house employees and researchers. There are also pre established sites throughout the prairie that have been used for various research projects ranging from: soil, pollinators, biomass, and invasive species.

The second half of my week was spent collecting pan traps and putting nest boxes out near the aspen stands with Scott. His work is focused on pollinators and shrubs. While he also collects bees with hand nets, for this trip he was using pan traps of various colors to collect bees in many of the same pre-established sites as Katie and Dr. DeBano. The pan traps are either white, yellow, or blue containers, filled with a soapy mixture, as pollinators are attracted to these colors. The containers are left at the sites for 48 hours and then collected. The pan traps also attract all types of other insects like flies, butterflies, spiders and mosquitoes. This bi catch is sorted out in the lab and saved for possible later research on biomass. Scott and I also hiked up to the aspen stand on Findley Butte Thursday afternoon to place nesting boxes for the season. These boxes will be collected at the end of the summer to see what pollinators are using them. The nesting boxes were attached to aspens of different age classes to see if there was variation in preference.

The second half of my week was spent collecting pan traps and putting nest boxes out near the aspen stands with Scott. His work is focused on pollinators and shrubs. While he also collects bees with hand nets, for this trip he was using pan traps of various colors to collect bees in many of the same pre-established sites as Katie and Dr. DeBano. The pan traps are either white, yellow, or blue containers, filled with a soapy mixture, as pollinators are attracted to these colors. The containers are left at the sites for 48 hours and then collected. The pan traps also attract all types of other insects like flies, butterflies, spiders and mosquitoes. This bi catch is sorted out in the lab and saved for possible later research on biomass. Scott and I also hiked up to the aspen stand on Findley Butte Thursday afternoon to place nesting boxes for the season. These boxes will be collected at the end of the summer to see what pollinators are using them. The nesting boxes were attached to aspens of different age classes to see if there was variation in preference.