Your eye lenses host one of the highest concentrated proteins in your entire body. The protein under investigation is called crystallin and the investigator is called Heather Forsythe.

Heather is a 4th year PhD candidate working with Dr. Elisar Barbar in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics. The Barbar lab conducts work in structural biology and biophysics. Specifically, they are trying to understand molecular processes that dictate protein networks involving disordered proteins and disordered protein regions. To do this work, the lab uses a technique called nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). NMR is essentially the same technology as an MRI, the big difference being the scale at which these two technologies measure. MRIs are for big things (like a human body) whereas NMR instruments are for tiny things (like the bonds between amino acids which are the building blocks of proteins). Heather employed OSU’s NMR facility (which has an 800 megahertz magnet and is on the higher end of the NMR magnetic field strength range) to investigate what the eye lens protein crystallin has to do with cataracts.

Dr. Elisar Barbar (L) and Heather Forsythe (R) with an NMR sample tube.

Heather with an NMR sample tube.

Your eye completely forms before birth, and the lens of the eye that helps us see is made of a protein called crystallin. This protein is essential to the structure and function of the eye, but it cannot be regenerated by the body so whatever you have at birth is all you will ever have. However, in the eye lens of someone affected by cataracts, the crystallin proteins become unfolded and then aggregate together. They stack on top of each other in a way that they are not supposed to. A person with cataracts will suffer from blurry vision, almost like you’re looking through a frosty or fogged-up window. While the surgery to fix cataracts (which basically takes out the old lens and puts in a new, artificial one) is pretty straight-forward and not very invasive, it isn’t easily accessible or affordable to a lot of people all over the world. Cataracts is attributed to causing ~50% of blindness worldwide, likely due to the fact that not everyone is able to take advantage of the simple surgery to fix it. Therefore, understanding the molecular, atomic basis of how cataracts happens could result in more accessible treatments (say a type of eye drop) for it worldwide.

This is where Heather comes in. There are different types of crystallin proteins and Heather zeroed in on one of them – gamma-S. Gamma-S is one of the most highly conserved proteins (meaning it hasn’t changed much over a long time) among all mammals, which tells us that it’s super important for it to remain just the way it is. Gamma-S makes up the eye lens by stacking on top of itself, making a brick wall of sorts ensuring that the eye lens retains its structure. However, research prior to Heather’s found that with increased age there is an increase in a modification called deamidation, which occurs in the unstructured loops of the gamma-S protein. Deamidation is a pretty minor change and is common in proteins all over the body, however in the eye lens if too much of it happens it no longer is a minor issue since it starts to disrupt the structure and protein-protein interactions of the eye lens. Heather’s collaborators at Oregon Health Sciences University found that there are two sites on the gamma-S protein (sites 14 and 76) where these deamidation events increase the most in cataracts-stricken eyes. It’s been known for a while that this deamidation is associated with cataracts however we never knew why it is associated with cataract formation because the changes caused by this modification were seemingly minor. This is how the Barbar Lab, and Heather specifically, became connected to this work since they specialize in studying unstructured proteins and protein regions, such as the loops present in gamma-S.

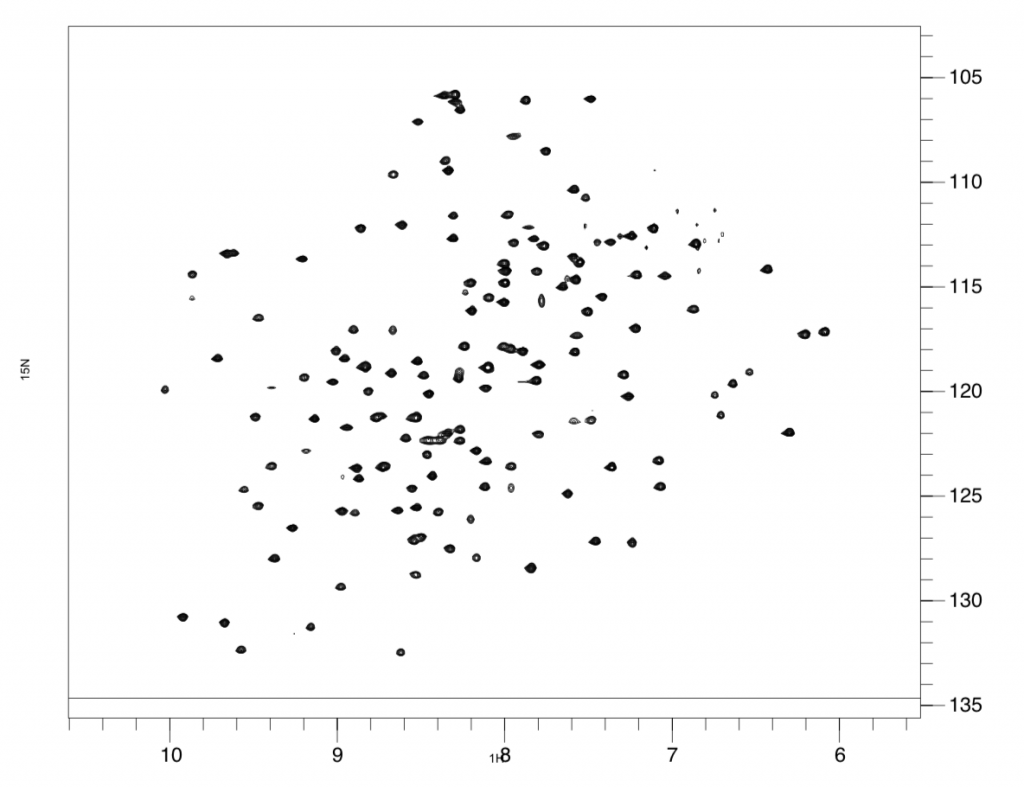

These deamidation changes are mimicked in the lab by creating two different mutants of the gamma-S protein’s DNA. Heather then compared the two mutants with the normal DNA by putting them through a series of experiments using the trusty NMR. The NMR is basically a large magnet that can make use of the magnetic fields around an atom’s nucleus to determine protein structure and motions. When Heather puts a protein sample into the NMR, the spins of the atomic nuclei will either align with or against the magnetic field of the NMR’s magnet. The NMR spits out spectra, which look like a square with lots of polka dots. This is essentially the fingerprint of the protein, unique to each one and extremely replicable. Heather can analyze this protein fingerprint since the different polka dots represent different amino acids in the gamma-s protein. Heather can compare spectra of the two mutants to the spectra of the normal protein to see whether any of the dots have moved, which would signal a change in the position of the amino acids.

After running experiments which measure protein motions at various timescales, from days to picoseconds, Heather discovered significant changes in protein dynamics when either site 14 or 76 was deamidated, however at different timescales. What this discovery means is that if both of these mutations are associated with cataracts and they are changing the same regions of the gamma-S protein, then these regions are likely central to changes resulting in cataracts. Therefore, research could be directed to target these regions to perhaps come up with solution to prevent and/or solve cataracts in a non-surgical way. The results of Heather’s study were recently published in Biochemistry.

Heather is from Arkansas where she completed her high school and undergraduate education. Living in a single-parent, non-academic home at this time, it took Heather a long time to figure out how to navigate the scientific and college-application scene, as well as even coming to the realization that science was something she was good at and could pursue. Despite receiving scholarships for college, she still had to work multiple jobs while in high school and college to have enough money for car-payments and gas to get to extra-curricular activities and volunteer jobs in the science field; things critical for graduate school applications. As a result, Heather is a strong advocate for inclusivity, striving to make things like science and college in general more accessible to low-income and diverse students. Heather’s decision to leave Arkansas and come to the PNW was inspired by advice she received from her undergraduate advisor who told her “not to go anywhere where you wouldn’t want to live. You will learn to love research, whatever it ends up being, but if you live in an environment that you don’t find fulfilling, then you are going to suffocate.”. Following this advice has lead Heather to where she is now – the senior in her lab where she has become a mentor to undergraduates, makes Twitter-famous Tik Tok videos (see below), goes on adventures with her dog Piper, and publishes cutting edge structural biology research.

To learn more you can check out the Barbar Lab website and Twitter page.

To hear more about Heather’s research, tune in on Sunday, September 29th at 7 PM on KBVR 88.7 FM, live stream the show at http://www.orangemedianetwork.com/kbvr_fm/, or download our podcast on iTunes!