Have you ever wondered why you see birds in some places and not in others? Or why you see a certain species in one place and not in a different one? Birds have wings enabling them to fly so surely we should see them everywhere and anywhere because their destination options are technically limitless. However, this isn’t actually the case. Different bird species are in fact limited to where they can and/or want to go and so the question of why do we see certain birds in certain areas is a real research question that Jenna Curtis has been trying to get to the bottom of for her PhD research.

Jenna conducting field birding surveys on Barro Colorado Island (BCI)

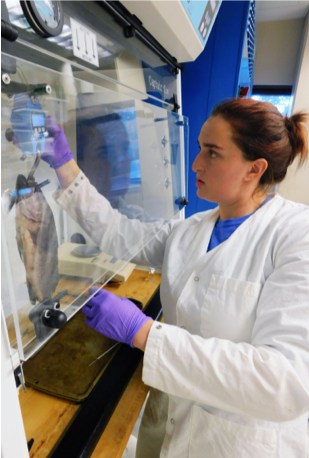

Jenna next to one of their (absurdly heavy) autonomous recording devices

Jenna is a 4th year PhD candidate working with Dr. Doug Robinson in the Department of Fisheries & Wildlife. Jenna studies bird communities to figure out which species occur within those communities, and where and why they occur there. To dial in on these big ecological questions, Jenna focuses on tropical birds along the Panama Canal (PC). PC is a unique area to study because there is a large man-made feature (the canal) mandating what the rest of the landscape looks and behaves like. Additionally, it’s short, only about 50 miles long, however, it is bookended by two very large cities, Panama City (which has a population over 1 million people) and Colón. Despite the indisputable presence and impact of humans in this area, PC is still flanked by wide swaths of pristine rainforest that occur between these two large cities as well as many other types of habitat.

A portion of Jenna’s PhD research focuses on the bird communities found on an island in the PC called Barro Colorado Island (BCI), which is the island smack-dab in the middle of the canal. To put Jenna’s research into context, we need to dive a little deeper into the history of the PC. When it was constructed by the USA (1904-1914), huge areas of land were flooded. In this process, some hills on the landscape did not become completely submerged and so areas that used to be hilltops became islands in the canal. BCI is one such island and it is the biggest one of them in the PC. In the 1920s, the Smithsonian acquired administrative rights for BCI from the US government and started to manage the island as a research station. This long-term management of the island is what makes BCI so unique to study as we have studies dating back to 1923 from the island but it has also been managed by the Smithsonian since 1946 so that significant development of infrastructure and urbanization never occurred here.

Now back to Jenna. Over time, researchers on the island noticed that fewer bird species were occurring on the island. There are now less species on the island than would be expected based on the amount of available habitat. Therefore, Jenna’s first thesis chapter looks at which bird species went extinct on BCI after the construction of PC and why these losses occurred. She found that small, ground-dwelling, insectivore species were the group to disappear first. Jenna determined that this group was lost because BCI has started to “dry out”, ecologically speaking, since the construction of PC. This is because after the PC was built, the rainforest on BCI was subjected to more exposure from the sun and wind, and over time BCI’s rainforest has no longer been able to retain as much moisture as it used to. Therefore, many of the bird species that like shady, cool, wet areas weren’t able to persist once the rainforest started becoming more dry and consequently disappeared from BCI.

Another chapter of Jenna’s thesis considers on a broader scale what drives bird communities to be how they are along the entire PC, and what Jenna found was that urbanization is the number one factor that affects the structure and occurrence of bird communities there. The thing that makes Jenna’s research and findings even more impactful is that we have very little information on what happens to bird communities in tropical climates under urbanization pressure. This phenomenon is well-studied in temperate climates, however a gap exists in the tropics, which Jenna’s work is aiming to fill (or at least a portion of it). In temperate cities, urban forests tend to look the same and accommodate the same bird communities. For example, urban forest A in Corvallis will have pigeons, house sparrows, and starlings, and this community of birds will also be found in urban forest B, C, D, etc. Interestingly, Jenna’s research revealed that this trend was not the case in Panama. She found that bird communities within forest patches that were surrounded by urban areas were significantly different to one another. She believes that this finding is driven by the habitat that each area may provide to the birds.

Jenna has loved birds her entire life. To prove to you just how much she loves birds, on her bike ride to the pre-interview with us, she stopped on the road to smash walnuts for crows to eat. Surprisingly though, Jenna didn’t start to follow her passion for birds as a career until her senior year of her undergraduate degree. The realization occurred while she was in London to study abroad for her interior design program at George Washington University in D.C. where on every walk to school in the morning she would excitedly be pointing out European bird species to her friends and classmates, while they all excitedly talked about interior design. It was seeing this passion among her peers for interior design that made her realize that interior design wasn’t the passion she should be pursuing (in fact, she realized it wasn’t a passion at all), but that birds were the thing that excited her the most. After completely changing her degree track, picking up an honor’s thesis project in collaboration with the Smithsonian National Zoo on Kori bustard’s behavior, an internship at the Klamath Bird Observatory after graduating, Jenna started her Master’s degree here at OSU with her current PhD advisor, Doug Robinson in 2012. Now in her final term of her PhD, Jenna hopes to go into non-profit work, something at the intersection of bird research and conservation, and public relations and citizen science. But until then, Jenna will be sitting in her office (which houses a large collection of bird memorabilia including a few taxidermized birds) and working towards tying all her research together into a thesis.

To hear more about Jenna’s research, tune in on Sunday, October 6th at 7 PM on KBVR 88.7 FM, live stream the show at http://www.orangemedianetwork.com/kbvr_fm/, or download our podcast on iTunes!