Geologists have considered an entirely new geologic era as a result of the impact humans are having on the planet. Some plastic material in our oceans near Hawaii along are hot magma vents and is being cemented together with sand, shells, fishing nets and forming never before existing material — Plastiglomerates. This new rock is a geologic marker providing evidence of our impact that will last centuries. Although rocks seem inert, that same plastic material floating around our oceans is constantly being eaten, purposefully and accidentally, by ocean creatures from as small as plankton to as large as whales and we’re just beginning to understand the ubiquity of microplastics in our oceans and food webs that humans depend on.

Our guest this evening is Katherine Lasdin, a Masters student in the Fisheries and Wildlife Department, and she has to go through extraordinary steps in her lab to measure the quantity and accumulation of plastics in fish. Her work focuses on the area off the coast of Oregon, where she is collecting black rockfish near Oregon Marine Reserves and far away from those protected areas. These Marine Reserves are “living laboratory” zones that do not allow any fishing or development so that long-term monitoring and research can occur to better understand natural ecosystems. Due to the protected nature of these zones, fish may be able to live longer lives compared to fish who are not accessing this reserve. The paradox is whether fish leading longer lives could also allow them to bioaccumulate more plastics in their system compared to fish outside these reserves. But why would fish be eating plastics in the first place?

Plastic bottles, straws, and fishing equipment all eventually degrade into smaller pieces. Either through photodegradation from the sun rays, by wave action physically ripping holes in bottles, or abrasion with rocks as they churn on our beaches. The bottle that was once your laundry detergent is now a million tiny fragments, some you can see but many you cannot. And they’re not just in our oceans either. As the plastics degrade into even tinier pieces, they can become small enough that, just like dust off a farm field, these microplastics can become airborne where we breathe them in! Microplastics are as large as 5mm (about the height of a pencil eraser) and they are hoping to find them as small as 45 micrometers (about the width of a human hair). To a juvenile fish their first few meals is critical to their survival and growth, but with such a variety of sizes and colors of plastics floating in the water column it’s often mistaken for food and ingested. In addition to the plastic pieces we can see with our eyes there is a background level of plastics even in the air we breathe that we can’t see, but they could show up in our analytical observations so Katherine has a unique system to keep everything clean.

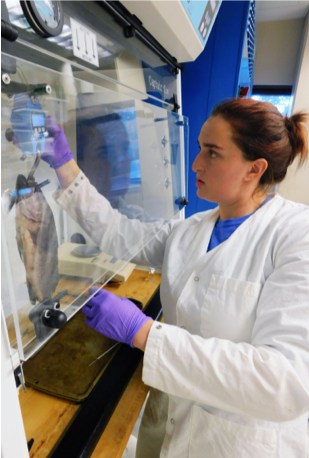

Katherine is co-advised by Dr. Susanne Brander who’s lab studies microplastics in marine ecosystems. In order to keep plastics out of their samples, they need to carefully monitor the air flow in the lab. A HEPA filtration laminar flow hood blows purified air towards samples they’re working with in the lab and pushes that clean air out into the rest of the lab. There is a multi-staged glassware washing procedure requiring multiple ethanol rinses, soap wash, deionized water rinses, a chemical solvents rinse, another ethanol, and a final combustion of the glass in a furnace at 350°C for 12-hours to get rid of any last bit of contamination. And everyday that someone in Dr. Brander’s lab works in the building they know exactly what they’re wearing; not to look cool, but to minimize any polyester clothing and maximize cotton clothing so there is even less daily contamination of plastic fibers. These steps are taken because plastics are everywhere, and Katherine is determined to find out just big the problem may be for Oregon’s fish.

Be sure to listen to the interview Sunday 7PM, either on the radio 88.7KBVR FM or live-stream, to learn how Katherine is conducting her research off the coast of Oregon to better understand our ocean ecosystems in the age of humans.

Listen to the podcast episode!

On this episode at the 16:00 mark we described how every time you wash clothing you will loose some microfibers; and how a different student was looking at this material under microscopes. That person is Sam Athey, a PhD student at the University of Toronto who also studies microplastics.