Prompt: As a healthcare professional, a colleague asks your opinion as to which HPV strains should be covered in a new treatment. Based on your reading from the Sarid and Gao 2011 article, what would your recommendation be, and when should the treatment be administered? What evidence supports your opinion? Keep in mind a cost/benefit analysis, as the cost of developing a vaccine for each strain can get very pricey! (You should not indicate “all of them” in your answer, unless you have strong supportive evidence).

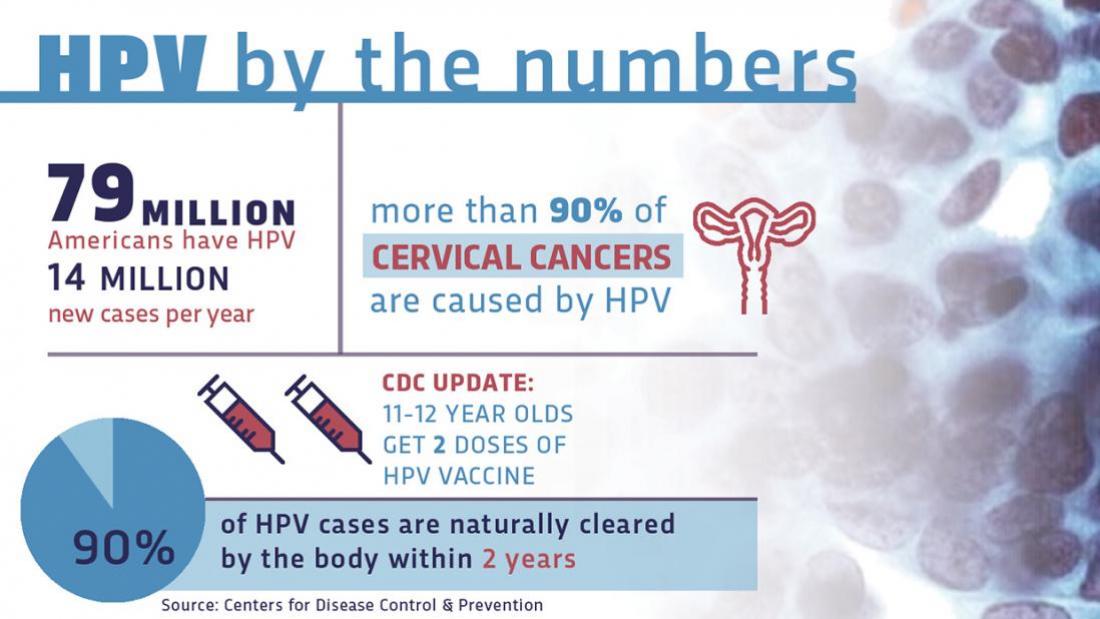

Human Papilloma Virus affects about 80 million people in America, and there are around 14 million new cases every year. HPV is a group of more than 150 related viruses that affect people in a number of ways, including some cases causing genital warts and cancer. In total, researchers have found 12 different strains of HPV that could be potentially carcinogenic to humans. 4 of these HPV strains have been deemed as “high risk,” and there are two others that have been proven through research to be carcinogenic. There are vaccines available for both HPV 16 and HPV 18 that have also proven effective against those particular strains, however, there are more HPV strains that are thought to be potentially high-risk. The interesting thing about HPV, and in my opinion, the good thing about it, is that between the 12 known strains of HPV, nearly all of them have been researched and seen to be one of the sole causes of cervical cancer in women. I say that this is the good thing about it because that means that scientists are only a couple steps away (hopefully) from treating, and possibly curing the causes for cervical cancer in the future. HPV has also been linked to a series of other cancers as well, which means that there is something needed to be done about possibly developing new vaccines that could cover more HPV strains.

Unfortunately, the issue with the development of a more efficient HPV vaccine that would protect people against more than just HPV16 and HPV18 is that the vaccine creative process takes more than just a lot of time and money, and it is already unlikely that they would be able to create a single vaccine to protect everyone from every strain of HPV. So, we know that there are 12 strains, and we also know that the probability of protection against every one of them is low. I propose, surely along with many others that the next step would be to develop a vaccine that works against the top 4 high-risk strains of HPV. With that, the risk factor of the virus causing cancer would be much lower than it is now. The idea is to continually lower risk factors. After we create a vaccine covering the 4 high-risk strains, then scientists could work to develop more protection/treatment and even work towards prevention.

As for when the treatment should be administered, I would say that it is more effective to administer a vaccine of this sort before the patients become sexually active in their lives. We know this, because HPV is a sexually transmitted disease, so we would all benefit from vaccinations before the late stages of puberty (sexual activity). I believe that this is a good time to administer the vaccine because 1. the patient is probably not yet sexually active, and 2. there should be no issue with the effectiveness of the vaccine diminishing before exposure to the virus.

References:

Sarid, R. and Gao, S. 2011. Viruses and human cancer: From detection to causality. Cancer Lett. 305(2):218-27.