For context, geology is defined as “the science that deals with the earth’s physical structure and substance, its history, and the processes that act on it” (Oxford Dictionary). What I find particularly enlightening about Kathryn Yusoff’s “A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None,” (particularly the chapter titled “Geology, Race, and Matter”) is the discussion of geology as a subject. Prior to reading this chapter, and subsequently researching to find the most accurate definition of geology, I was under the impression that geology solely dealt with the earth’s structure. I believed that geology simply dealt with topography and earth’s natural phenomenon. I wasn’t entirely incorrect, but I was omitting an entire topic focused on by geologists. So, as I’ve learned, geology not only deals with topography but it deals with the history of the earth and “the processes that act on it” (which can be expanded to include the actions of humans). Knowing the true definition of geology and having the entire picture allowed me to understand the article at a greater capacity and truly interact with its contents.

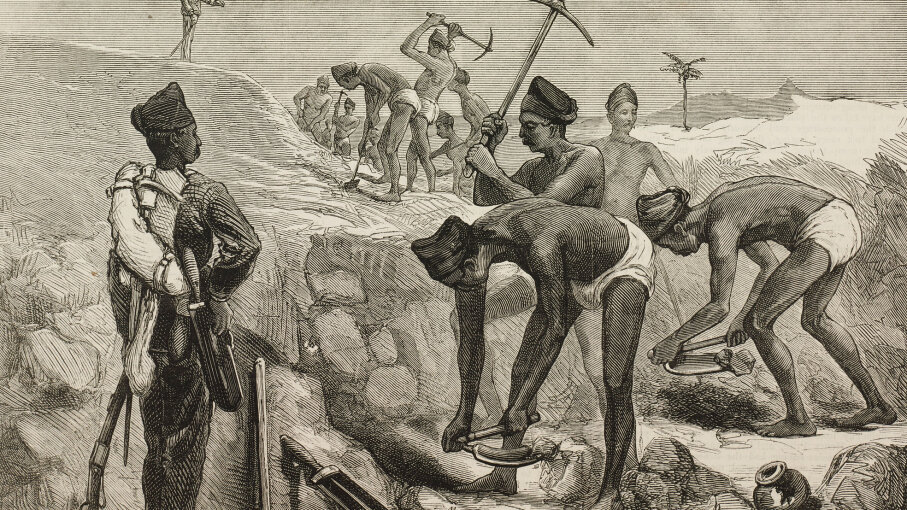

In “A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None” Kathryn Yusoff argues that our concept of what the Anthropocene is is limited. The world’s view (or the majority of the world’s view) of the Anthropocene is lacking, just as my concept of the definition of geology was. Yusoff argues that this omission is harmful. Yusoff argues that the history of slavery is incredibly important to the idea of the Anthropocene. Europeans colonial desires (which displaced native peoples and fueled the destruction of the planet by humans) were enabled by slavery and that it must be discussed. The idea of an Anthropocene is incomplete without a reason as to why and how we started this ecological crisis. Additionally the effects of slavery can be seen today, especially in the modes that we use to destroy the earth. In the publication Yusoff wrote, “the complex histories of those afterlives of slavery continued in the chain gangs that laid the railroad and worked the coal mines through the establishment of new forms of energy, in which, Stephanie LeMenager (2014, 5) comments, ‘oil literally was concieved as a replacement for slave labor.’” Along with the idea of Europeans using slavery as a means to wreck havoc on nature, Yusoff argues that we must talk about the social side. We must acknowledge the effect that slavery has had on the Afircan American population and the “Antiblackness” that followed.

A section of the publication that I felt summarized that point (or at least part of it) that Yusoff was trying throughout to make clear is as follows: “ Rendering subjects as inhuman matter, not as persons, thereby facilitated and incorporated the historical fact of extraction of personhood as a quality of geology at its inception.”