In her book, “A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None”, Kathryn Yusoff discusses how modern civilization has failed to “properly identify its own histories” (Yusoff 13). She credits the victors of history with incorrectly writing their own history, often leaving out, dehumanizing, or ignoring the exploitation of other cultures. Specifically, how White history does this to primarily black and brown people. Yusoff mentions multiple places where history has come up short, and asks us: who are we to define a new age if we cant even get our own history accurate?

I think that Kathryn Yusoff defies the common idea of an Anthropocene in quite an interesting manner. Instead of denying its potential existence, she instead denies its potential infancy. By asking us to “consider what historicity would resist framing this epoch as a ‘new’ condition that forgets its histories of oppression and dispossession” (15). There is no doubt in my mind that our history and geology are immensely incomplete in the way Yusoff describes, leaving out essential details that dehumanizes, and incorrectly defines many past events.

However, in the grand scale of things, I don’t see much vitality in understanding how we reached the Anthropocene. Rather, the fact that we are in one matters. And to me I don’t see how the points of incorrect history and geology effects that. And so while I agree with almost all of the points in the text that I understand, I struggle to find how it relates to the current issue at hand. I very much understand that I likely misinterpreted this text or took some of its points out of context or at least I hope that is the case as it did raise quite interesting points. They were just not ones that necessarily change how we should approach our rapidly incoming doom that is the Anthropocene. I hope to come to a better understanding of the text in next class.

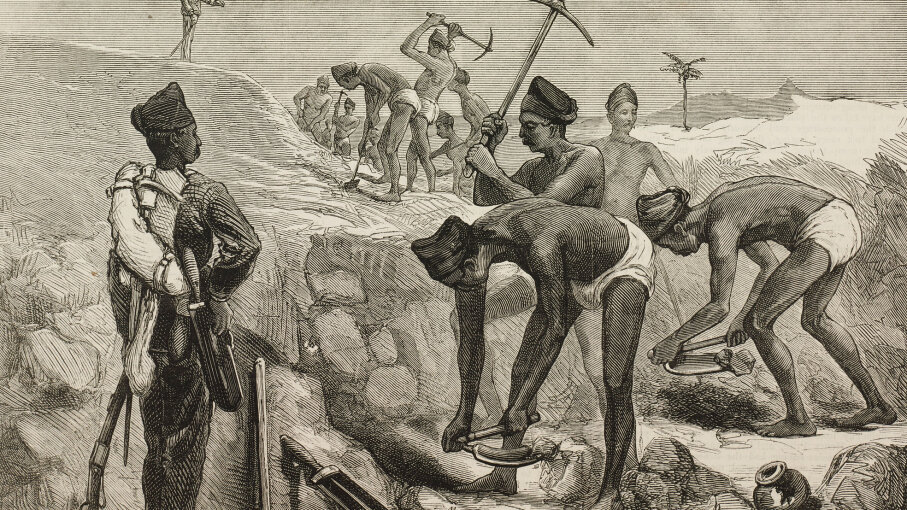

Picture: whytoread.com